Corona Testing Priorities

Covid-19 has generated many urban myths. One very apt one is about the health minister of a certain third world country who was asked why his country didn’t have any coronavirus patients; he responded by saying: “because we have not conducted any coronavirus tests.”

Covid-19 tests form the basis of the Corona policy response; be it isolation of patients, priority of hospitals, decisions for total or partial lockdowns – all are linked to testing. If there are no tests, there are no confirmed Covid-19 patients and therefore there is no reasonable basis for optimal allocation of resources and assigning priorities.

One country that has effectively used testing to not only control the spread of the novel coronavirus but also to avoid lockdowns is South Korea. Its response has been so effective that the country managed to hold its General Elections on April 15, 2020. The turnout of 66 percent has been the highest in 16 years. Despite this record turnout, just 15 days later ie on April 30, South Korea announced that it had no new cases to report for that day. How was South Korea able to manage all that?

South Korea’s response to Covid-19 has largely been shaped by its experience with the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) which killed 36 and infected 186 South Koreans in 2015. For South Korea, one of the main takeaways from MERS was the importance of testing and the subsequent contact tracing. This was such a strong realization that following MERS, South Korea enacted legislation that smoothed out the legal impediments towards approval of testing and the placement of necessary contact tracing measures. The impact of this preparation was seen in South Korea’s response to Covid-19, as it approved Covid-19 tests in record time and put in place effective contact tracing measures.

Given the reluctance of our prime minister to impose a lockdown, it is indeed strange that he almost never mentions South Korea, a country that has been able to control Covid-19 without lockdowns. It should be obvious that the US, UK, and some other European countries largely failed not because all efforts against Covid-19 are futile, but because their leaderships are guilty of criminal mismanagement and incompetence. The fate of US, UK and many other first world countries could have been different had their governments taken effective and timely measures. The failure of these rich countries should not be a reason for our ministers and their advisors to shrug shoulders, South Korea’s examples shows that horrific death tolls can be avoided through efficient and timely use of resources.

So how does Pakistan compare against South Korea when it comes to testing? One measure is to look at the total number of tests conducted as a proportion of population. As per the World Meter website, for May 3, 2020, South Korea has one of the highest proportion globally at 12,365 tests per million population, in comparison Pakistan was at a mere 962 tests per million population.

But our weakness in testing at the national level is even more pronounced on the provincial levels. The worst is Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where testing stood at 520 tests per million population on May 2, 2020 – at almost half the national average. Punjab was slightly better at 664, followed by Balochistan at 813. Among the four provinces, only Sindh scored higher than the national average, at 1274 tests per million of population.

The situation becomes much worse when one goes down to the district level. I could not find the district level testing coverage for other provinces. However, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa shared its district level testing statistics till the 16th of April, after which Khyber Pakhtunkhwa also stopped reporting on district level testing numbers. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s data till April 16, 2020 reveals that three districts – Peshawar, Mardan and Swat – accounted for 41 percent of the five thousand tests done by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa till then. Despite their relatively larger populations, Mardan had a testing coverage of 320 tests per million population, Swat was at 223 and Peshawar at 206, much higher than the provincial average which was at 137 tests per million population by that day.

The districts of the ex-Fata region were particularly worse off, as Mohmand Agency showed a coverage of mere 15 tests per million, South Waziristan was at 32 and North Waziristan at 42. The three districts of the Kohistan region – Kohistan Upper, Kohistan Lower and Kolai Pilas – had had no tests by the 16th of April. Considering that travel history has been a critical criterion for qualifying for testing, it’s important to note that a considerable number of Pakistanis from ex-Fata work overseas. What percent of those have come back before Peshawar airport’s screening requirements were made more stringent?

Also, given that 77 percent of cases in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa were caused by domestic spread, then how far is Mohmand Agency from Peshawar and Kohistan from Swat? Is it that easy to presume that these peripheral and under-developed districts would be that immune, and deserve such low levels of testing? In fact, considering the education and awareness levels of underdeveloped districts, it would be safe to conclude that knowledge and practice of precautions might be much lower in underdeveloped districts than in developed ones.

It would be wrong to assume that testing priorities in other provinces are different from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. In fact, if one plots district-level Corona incidence against the Human Development Index (HDI) score of the districts across Pakistan, it reveals a positive relationship – districts with high HDI scores are also districts with high incidence of Covid-19. One explanation could be that districts with higher HDI also tend to have bigger populations, like Karachi and Lahore. However, there are exceptions such as Islamabad, which constitutes one percent of Pakistan’s population and almost two percent of Pakistan’s Covid-19 patients. It is also the district that has a testing coverage of 5,922 persons per million people, more than 6 times the national average on May 2, 2020.

Given these trends, it may very well be the case that our Corona priorities and efforts, which are tied to testing for the virus, are geographically focused on our most developed districts. This means that districts with low or even nonexistent health facilities might be getting ignored in the tracking and isolation efforts that that are currently underway. Call it oversight or negligence, but ignoring less developed districts can have major implications in the near future. By dragging our feet on testing as well as lockdowns, our prime minister is wishing for a situation where he can have his cake and eat it too. Human history has shown that that is never a good strategy.

This was first published in The News on the 8th of May, 2020

Financial Inclusion in Pakistan

One of the most common mismatches in life is that between income and consumption. It’s good when income exceeds consumption, but explains all the downsides of poverty when it is the other way round. The art of dealing with this mismatch is called ‘consumption smoothing’, and most of us do it throughout our lives.

Modern banking and finance has largely evolved to facilitate humanity’s struggles with consumption smoothing; the financial losses from an unexpected car crash can be mitigated with insurance, a sudden rise in business expenses can be met with a loan, and savings apportioned for the future can earn interest if kept in a savings account rather than at home.

There is a term for those who can avail the benefits of formal banking and finance; they are called the ‘financially included’. These are individuals with a formal financial account, be it a bank account or a mobile money account. As per World Bank estimates, for 2017, 69 percent of the world population is thought to be financially included. However, for Pakistan, financial inclusion is quite exclusive as the World Bank estimates only 21 percent of the Pakistanis to be financially included.

Pakistan’s financial inclusion strategy has a very ambitious goal for its Vision 2020, as it aims at 50 percent of its adult population to have a bank or mobile money account by next year. The efforts so far have mainly been focused on relevant issues such as lack of financial awareness and financial literacy, the complications of account registration, as well as financial infrastructure issues etc.

While these are valid constraints, in my opinion, limited access to loans might be the most crucial constraint that is resulting in low financial inclusion levels in Pakistan. Loans are a crucial lifeline in cases where expenditure exceeds income, and their availability can mean that households don’t have to choose between essential expenses, such as the education of a child and the health of a parent. It is this availability of financial loans that incentivizes formal financial behaviour; paying for goods through a credit card or a mobile wallet might mean more than convenience if the transaction adds to one’s credit score.

This incentive is inbuilt into the concept of banking, where individuals can choose to be just depositors or depositors and borrowers as per their financial circumstances. A bank account then becomes more than just a vault for cash or an option of money transfer, the possibility of loans makes it a source of financial security. Therefore, it is very likely that the lending priorities of commercial banks play a role in convincing the financially excluded to become financially included.

The latest figures from the State Bank of Pakistan show that our commercial banks have invested approximately Rs7 trillion in government securities. This constitutes around 50 percent of our overall banking deposits. For India, the same is at 28 percent. The government’s direct borrowing from commercial banks is at Rs0.8 trillion, which is another six percent of deposits. Meanwhile, ‘personal loans’ – loans given to households – stand at a mere five percent of deposits, compared to 16 percent in India and even higher in more advanced countries.

The net effect of this massive borrowing by the government is a crowding out of the private sector; a relevant indicator that captures loans for household and private businesses is the amount of domestic credit as a percentage of the GDP. On this measure, Pakistan is at a mere 19 percent, comparable to countries such as Haiti and Lesotho. Meanwhile, for India the same is at 50 percent and for Bangladesh at 47 percent.

The prime responsibility of a bank is to maintain its profitability and in the current scenario, lending to government is perhaps a better alternative than considering households as a potential market. When seen in this context, all the excitement about the use of technology in finance, for increasing financial inclusion, seems a bit misplaced. One of the biggest advantages that modern data processing technology can provide is to enable banks to sift low-risk borrowers from high-risk ones by analyzing massive datasets, like those of cellphone usage patterns etc. However, for banks to invest in more innovative credit risk assessments they need to be looking to earn money through more risky lending. What incentive do banks have in developing more rigorous screening abilities when the government is offering a much safer alternative?

It would be easy to simply say that the government should reduce borrowing from the banking sector. However, Pakistan is faced with a massive income and expenditure mismatch at our national level as well. Consider the fact that our direct tax collections are approximately equal to our defence spending, and our indirect tax collections are almost the same as our debt servicing payments, both amounting to around 72 percent of our revenues. How exactly will the country run, if the government doesn’t borrow?

The debate on financial inclusion in Pakistan and its targets have to be linked to our fiscal realities. It is easy to categorize the financially excluded masses as being unaware of the promises of formal finance, but would the current offering of financial products incentivize them to register for a formal account even after they become aware?

The mere registration of a bank or mobile money account shouldn’t be seen as an end. Innovations such as digitally submitting utility bills or electronic remittance payments are great but these mostly provide convenience, not financial security. For our less privileged and mostly financially excluded masses, consumption smoothing means a constant search for loans of small amounts and short duration. That is one pain point that our formal financial sector should be able to relieve, for formal account-holders to be truly considered as financially included.

However, for that to happen, our poor have to become profitable for our banks. And that won’t be possible as long as our banks have to ‘choose’ between the low collateral of the poor and the sovereign guarantee of the state of Pakistan.

This article was first published in The News on 12 September, 2019

Peshawar’s Culinary Heritage

Cities are known for many things, such as historical buildings, or festivals for that matter. But one thing that is of interest to many, is food. And as per my biased assessment, when it comes to meat dishes Peshawar is the best, the unbiased assessment would be that it is definitely one of the best.

However, it is disappointing to see Peshawar not being recognized for its indigenous dishes. Instead, it is often praised for dishes for which its offerings are probably second best. Take the famous Namak Mandi for instance, Charsi tikka and others make a great Shinwari barbecue and Karahi, but for the best you need to travel to the Shinwari heartland in Khyber Agency, which is also the place of origin for this style of barbecue. Similarly, for chapli kabab, you have old and established names like Jalil Kabab in Peshawar. However for much better chapli kababs you need to travel to Mardan, which quite possibly is the birthplace for the dish. Kabuli Pulao is another one that is ascribed to Peshawar. Even GEO’s, otherwise excellent, documentary on biryani, assigned the Kabuli pulao to Peshawar. And despite the fact that Baba Wali in Karkhano market does a great Kabuli pulao, the name of the dish itself is a giveaway. I am sure Kabul has much better Kabuli pulao than what is available in Peshawar.

The ground zero for any dish is likely to have its best version as well. That could be because the institutional memory of its outlets, that made the dish famous, is likely to be longer than those in other places. Furthermore, it is likely that the city will have the highest competition for that particular dish. And competition, almost always, translates into better quality.

Peshawar’s indigenous culinary map has many iconic dishes that often get ignored. Two of those come together in the Peshawari “Khoncha”. The “Khoncha” is not a dish but it’s a tray that is used to serve wedding food. The name probably is a misnomer of the Hindi word “Khomcha”, which refers to the tray carried by food vendors. However, in Peshawar the Khoncha has been the traditional symbol of Peshawar’s wedding hospitality, a symbol that is fading fast into oblivion.

The Khoncha could feature around 6 to 8 distinct dishes and the amount of food is enough for 4 to 6 people, depending on the host’s choice of seating. A regular khoncha is arranged with a tray full of Channa Mewa pulao in the center, on top of the pulao are 4 zaafrani seekh kababs, which are covered by a Peshawari naan. On the side is a complete fried chicken, and next to it is a bowl of daal mutton qorma (at times kofta daal qorma), also included is a plate of saag gosht, or a mutton/lamb dish called “speena ghwakha” (white meat). Each corner of the khoncha has a bowl of kheer or firni, with one small dish of alu-bukhara muraba for all to share as a topping on the kheer/firni. My fondest food memories from childhood are about getting together with my cousins and friends over a khoncha. But such is the change in times that I couldn’t find even a single shareable pic of the Peshawari khoncha on google images. Will make sure to click one the next time I come across a khoncha, but I am not sure when that will be.

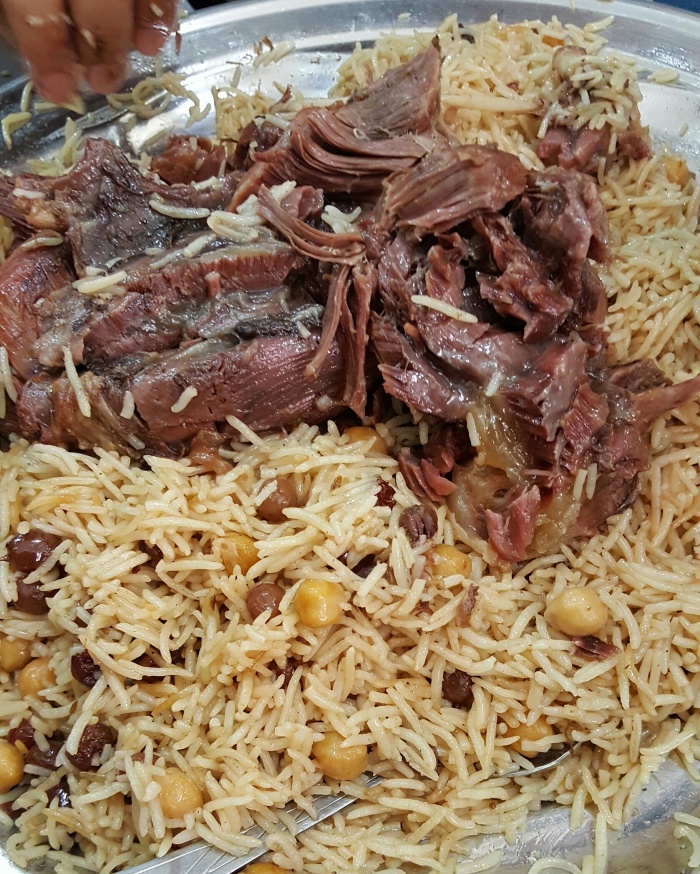

The Khoncha includes two of Peshawar’s signature dishes. The first is Channa Mewa Pulao. Not to be confused with Kabuli pulao, this is a dish that is quite distinct among the rice dishes of Pakistan. Apart from its distinctive mix of chanra (chick peas) and mewa (raisin), the pulao is also different because it is not made from regular basmati rice, instead it is made from the much sturdier, parboiled variety of basmati called the “Saila”. A good chanra mewa has to have good beef, and within that the most coveted pieces are of shank meat, popularly known as “machli”. In Hindko it is often referred to as “jhal pulao”, “jhal” from “jhala” meaning crazy. The reference being that you eat it like crazy.

The best Chanra Mewa pulaos that I have had, have been at walimas. Before Shadi halls became en vogue and dinner preparation became totally outsourced, the taste and quality of walima dinners used to be taken very seriously by most hosts in Peshawar. Meat preparations would begin the night before the feast and celebrity chefs like Malang Sher would have to be booked well in advance. The hosts would also be involved in ingredient shopping; buying good meat and aged sella are things that some hosts would make extra effort for.

However, in recent times, Peshawar too has fallen prey to this whole biryani-fication trend at weddings that is sweeping northern Pakistan. In the case of Peshawar, this has coincided with the move to shadi halls. In my experience, Peshawar is probably the worst when it comes to mimicking biryani, and it’s a tragedy that it is being done at the expense of its own Channa Mewa pulao. But you can still get a good Channa Mewa pulao over the counter. Laziz pulao in Shuba bazar does a very good job, and they serve pieces of beef shank on demand as well.

Chanra Mewa Pulao at Laziz Pulao Peshawar. Picture courtesy of Peshawar X on Flickr

Another signature dish, which also goes so well with chanra mewa pulao, is the Zaafrani seekh kabab. This is quite different from seekh kababs in other places. The meat is minced very fine and is mixed with lamb fat. Kababs with real Zaafran might be hard to find, as haldi has replaced Zaafran, but still Peshawar’s Zafraani kabab is a dish that deserves more appreciation.

Peshawar’s Zaafrani Seekh Kabab – Pic courtesy Chefling Tales

The Zaafrani kabab is also quite versatile. In Peshawar, it is common to see these kababs stored in freezers, waiting to be thawed and then served with afternoon tea along with mint chutney. It can also be turned into a karahi with tomatoes and green chillies. The best place for having these is Chowk Nasir Khan.

This next dish would qualify for the title of the most authentic Peshawari breakfast. “Paanchay” are beef trotters or payay. The name might have a turkish/central Asian origin, as “Pacha or paça” is a Turkish variety of soups that usually involves offal meats. Peshawar’s Paanchay also include head and tongue meat at times. It is also very low on spices when compared to payay from Punjab.

Although there are many good outlets, Nikka Paancha farosh in Tehsil gor gathri and Haji Mohammad Sadiq in Jehangir Pura are two of the oldest and most famous names. Legend has it that, Nikka Paancha Farosh’s pir told him to not sell more than one pot a day. Apparently that advice is still followed as the shop runs out of stuff quite early in the morning.

The Paanchay are cooked overnight in a large earthen vessel over a slow flame, usually over wood fire. The served dish includes chunks of beef trotters, along with beef, other offal meats could also be added after which a dash of red roghan (desi ghee with food color) is added followed by a splash of bone marrow, and a sprinkling of garam masala. This dish is certainly not for the faint hearted.

Peshawari Paanchay – Pic courtesy PeshawarX

Paanchay are eaten with the Peshawari naan, which again is a food icon worth mentioning. Peshawar’s naans compliment almost every meat dish, and are a must when having Paanchay. Another dish, called “Kulla”, is an ideal combination of these two. In a kulla, Peshwari naans are mashed in Paanchay curry, and then the various meats are placed on top. The sellers do the mashing in a particular way that ensures that the bread is properly soaked in curry.

I am sure I have missed other dishes, and many might disagree with my way of looking at the food of Peshawar. But the next time you are in my city, please do give these dishes a try. I assure you, no other place can outdo Peshawar in these.

Deflections Galore

Pakistan’s media seems to have a weird relationship with the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM). From Naqeebullah making the headlines, to an almost complete silence during the Islamabad dharna, to Manzoor being invited to prime time talk shows, our media’s focus have followed a pattern that hasn’t matched the exponential increase in PTM’s popularity. Some are arguing that this shift of media focus was because the media “ignored” the plight of Pashtuns. Takes some stretch of the imagination to say that the smaller crowd in Karachi, protesting against Sindh government and Sindh police, was worthy of headlines across all channels. But the much larger crowd in Islamabad, protesting not only against Sindh police but also against the military establishment, was not worthy of the same?

But in any case, whether ignored or faced with a blackout, the PTM recently did get a relatively higher proportion of time on our talk shows. However, the increased focus came with a set of deflections that are taking the focus away from the very basic demands of PTM. The following are four such deflections that seem to be in fashion these days.

First, is the allegation that Manzoor Pashteen and PTM are guilty of “sedition”, because they are disrespecting this country’s institutions; institutions that have given us martyrs. I just fail to understand linking martyrs to issues of institutional performance. Our Police has given thousands of martyrs, some of whom grappled suicide bombers to stop them from detonating in larger crowds. WAPDA, has a long list of line-men who were martyred while fixing high intensity powerlines. As Pakistanis we should have nothing but respect for our martyrs and eternal gratitude towards their families. Because, martyrdom is the ultimate sacrifice for our country, and there is nothing we can do to repay our martyrs or their families.

However, should police performance not be scrutinized out of respect to Police martyrs? The problem of load shedding and line losses should not be deliberated upon because it would be an insult to the martyrs of WAPDA? Of course not, and we don’t. Then why should we make an exception in the case of our military?

Second, there is an attempt by some quarters to declare the arrest and possible punishment for Rao Anwar to be the answer to PTM’s demands. Such reductionist thinking ignores the thousands of Naqeebs who have died under similar circumstances and hundreds of Rao Anwars who are suspected of carrying out these killings. The outpouring of sympathy for PTM wasn’t just for Naqeeb, there are many more who have been killed in an extrajudicial manner and not only by Rao Anwar. Similarly, extra judicial killings is not the only issue raised by PTM, there is the issue of missing persons, humiliation at military checkpoints, and landmines in Waziristan which have nothing to do with Rao Anwar, so how will his trial be a response to these demands?

Third, there are some who believe that the merger of FATA with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa will meet PTM’s demands. However, missing persons is as much a problem of FATA as it is of KP and Balochistan. In fact, as per the latest official statistics from the Commission on Inquiry of Enforced Disappearances, KP accounts for 55% of the cases collected by the commission. This is the highest proportion of missing persons among all regions of Pakistan, including FATA. Similarly, issues with checkpoints are not limited to FATA; recently there was a protest in Swat after an infant died in the waiting line of a military check point, while on the way to the hospital. So how will a merger with KP, a province with missing persons and humiliation at check points, magically solve these problems in FATA?

Fourth, there have been many who are worried about the public support for PTM in Afghanistan. The worry being that this is an attempt at secession. This particular brand of mind reading analysts make an extra effort in ignoring Manzoor’s repeated pleas that he is demanding his constitutional rights as a Pakistani. Recently, in an interview with the Voice of America, Manzoor encouraged Afghans to take up their issues with the Afghan government through peaceful protest, just like the Pashtuns of Pakistan are doing.

To understand Manzoor’s appeal to the Afghans, one has to first appreciate his oratory skills. A brilliant piece by Maham Javaid for The News on Sunday is a must read for anyone trying to understand Manzoor’s appeal. The other aspect that is more relevant to Afghan psyche is Manzoor’s insistence on the need for peace. The war on terror has disproportionately affected the Pashtun belts of both Pakistan as well as Afghanistan. This shared sense of adversity has resulted in a yearning for peace expressed through poetry, songs and other mediums that both sides can relate to. More importantly, this cross border consoling started long before Manzoor came on the scene. So when Manzoor speaks about the costs of war and the need for ensuring peace, and that too in Pashto, he has sympathetic ears on the other side of Durand line as well. In all of this if, Ashraf Ghani, an elected president, tweets in favor of PTM then that is more to respond to the sentiments within his own voter base rather than an attempt at sowing “discord” in Pakistan.

It seems that by not committing sedition and by not demanding secession, Manzoor has disappointed many “patriotic” hawks who seem to be programmed to deal only with “traitors”. Their efforts to misrepresent Manzoor seem quite desperate, and an insult to the intelligence of the masses they are trying to convince. Manzoor is making his case as a Pakistani and in constitutional terms, it is only fair that any weakness in his arguments be pointed out in constitutional terms as well. If there is one lesson that our state can learn from our dealings with Bengalis as well as Balochs is that deflection never solves problems, it only exacerbates them. Let’s not repeat the same mistakes with the Pashtuns as well.

An edited version appeared in The News on 12th of April, 2018.

Malala and APS

Malala is back, and so are her haters. Just scan through any Facebook post on Malala’s injury or achievements, and you will see the irreverent “laugh” or “angry” emoticons taking over the “like”, “sad” or “love” emoticons. Scan through the profiles of this lot and they seem to be quite a diversified group when it comes to appearances.

What unites them however is their penchant for coming up with ridiculous conspiracy theories to discredit Malala. While they fail on every account, the only success that they have had so far is to disprove Malala on her faith in education as the cure for hate and intolerance. On that front, the educated among this lot disprove Malala with their mere existence.

In my opinion, this hate for Malala lies in our pre APS narrative on terrorism. Where Taliban were portrayed as “our people” fighting us because we are part of “Amreeka key jung” (US war on terror). These were the days when Imran Khan would assure us that the Taliban would disarm as soon as we disassociate ourselves from the US war on terror. Similarly, Shahbaz Sharif was reminding the TTP of common foes and in so doing making a case for them to spare Punjab. The only solution proposed by this lot was to conduct “Muzakrat” (negotiations) with the Taliban.

The attack on Malala challenged the narrative of this Muzakrat group of political parties. A helpless, 15 year old, girl was shot point blank and the TTP was proudly taking responsibility. She wasn’t attacked because she supported drones, neither was she a politician that allied with the US. All she wanted was to get an education, a dream child for any parent across Pakistan. Introspection at the national level would have been a natural consequence, probably resulting in calls for a reprisal against the TTP. But at stake was the “muzakrat” narrative that was to be a vote winner for the 2013 elections, and out came its defenders with conspiracy theories and slander campaigns.

We have come a long way since those days. Ever since the “Muzakraat” group of parties won the 2013 elections, Malala has been vindicated over and over again. She was vindicated when PML-N, PTI, JI and JUI-F, agreed to launch operation Zarb-i-azb against the TTP. Malala’s 2011 insistence on the need to punish Fazlullah was a timely warning, well ahead of Fazlullah’s massacre of APS children in 2014. Malala’s 2011 plea to the military to control its highhandedness in Swat operation is presently being echoed by thousands of those marching under the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement. Most Malala haters today would agree with what Malala of 2011 stood up for, yet their selective amnesia compels them to still call her a drama, and question her achievements.

To understand Malala’s achievements one has to understand the concept of “common good”. Common good refers to the interests that are shared by everyone in a society, whether it’s the freedom of speech, religion or for that matter the freedom to get an education. It is the glue that holds a society together, as these common interests represent the overlap of our incentives. A contribution to the common good could be volunteering to pick up trash on a hiking trail, or, in the case of Malala, taking a bullet for the right to be educated.

If you are someone who thinks that education is a waste of time, then you are absolutely right about Malala, she hasn’t contributed much. But if you are the parent who thinks that education is important for you children. Then imagine how much their education means to you? What would you do if a band of armed thugs stopped your children from going to school? Will you encourage them to speak openly for their rights at the risk of their lives? Will you have the courage to speak up?

If you were an adult Pakistani back in 2012, then it is very likely that you chose to remain silent, mostly because of fear. There is no shame in admitting that, but then it is shameful to not recognize the courage shown by Malala and her parents when they chose to speak out against the Taliban menace in Swat. They did it not only for themselves, as they too had the option of remaining silent like the rest. Instead, Malala, backed by her parents, took a bullet for the common good that is the right of schooling for Pakistani children. She took a bullet so that young girls like Arfa Kareem were not forced to stop pursuing their education. She took a bullet to highlight the danger that children like Waleed Khan faced for the “crime” of going to school.

We humans recognize and appreciate displays of courage, especially when done for the common good. Malala’s global recognition was not for her intelligence or the severity of her injury but for her bravery. It is indeed bewildering that many of those who, back then, didn’t even let out a whimper out of the fear of the Taliban, now fail to understand what makes Malala special.

Malala haters need to resolve their internal contradictions. The pre-requisite for mourning the APS massacre would be an apology to Malala. That’s because her “drama” was to warn us about the dangers posed by the likes of Fazlullah. It was the TTP that took responsibility for not only APS but Malala’s attack as well. Consistency demands that we either declare both these attacks as dramas, or consider them as attacks on our children; children who paid the price for the stupidity and/or fearfulness of their elders.

A slightly edited version appeared in the daily The News on the 7th of April, 2018

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, PTI and 2018

In the aftermath of the by-elections of NA-4 in Peshawar, many have predicted PTI’s victory to be an indication of a possible second term for PTI in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). However, in my opinion this assessment doesn’t hold to scrutiny when seen in the norms surrounding by-elections in Pakistan, as well as the regional voting patterns within KP.

In the follow up to General Elections (GE) 2013, a total of 19 National Assembly (NA) by-elections were held across all the four provinces on seats which, like NA-4, were won by provincial incumbents in 2013. The results show that provincial incumbents won 16 of these 19 seat. It is likely that incumbency becomes a disadvantage only after it is over, not before that. The predictive power of by-election wins could be seen in ANP’s win of NA-9 Mardan in the 2012 by-elections, i.e. just one year before ANP’s electoral rout out.

Now to the electoral results in KP, which like most things KP are often subjected to some very orientalist interpretations; where the province is portrayed as a united entity that always punishes bad governance. This fits perfectly with the vengeful and righteous “Khan saab” stereotype of Pakhtuns that seems to be popular in Pakistan.

However, the regional voting patterns in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa paint a more nuanced picture. KP is usually divided into four regions, each with its own voting behavior. The anti-incumbency voting backlash exists but is limited to Peshawar valley (districts of Peshawar, Nowshera, Charsadda, Swabi and Mardan), a region that accounts for 36 of the 99 seats in KP’s provincial assembly. In the northern districts (Malakand, Swat, Chitral, Bunair, Shangla, Dir upper and Lower) only Swat votes in a manner that is similar to Peshawar valley, the rest of the districts usually give an overall fractured mandate. The Hazara division has always been a stronghold of the dominant brand of Muslim League, and the Southern Districts (Kohat, Karak, Hangu, D.I. Khan, Bannu, Lakki Marwat, and Tank) lean more towards JUI-F. Both Hazara and the Southern districts also account for a majority of KP’s independent candidates; after the 2013 elections, of the 14 independents, 11 were from these two regions.

These regional voting patterns have created a situation where it is highly unlikely for one party to hold a majority in KP; as is the case in Sindh and Punjab. Therefore, since 1988, provincial governments in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (former NWFP) have almost always been formed by parties winning the center, as federal ministries and committees give them a powerful leverage when parlaying for alliances.

Since 1988, both PPP (1988, 1993) and IJI/PML-N (1990, 1997) formed governments in NWFP during their federal terms, a similar arrangement took place in the 2008 ANP-PPP government. It is likely that had Islamabad seen a PM return for a second consecutive term during this time, Peshawar might have seen a CM return as well.

However, there have been three exceptions to this pattern; first was the short lived government of PML-N’s Pir Sabir Shah in 1993, when PPP had won the federal government. Mr. Shah was brought down within five months and replaced by PPP’s Aftab Sherpao.

The second exception were the controversial elections of 2002 when the MMA broke through traditional voting patterns and secured 48 out of 99 seats in the KP assembly, thus able to form the government on its own.

The third exception was in 2013 when PTI formed the Government in KP. However, this wasn’t because of an overwhelming mandate; KP’s seat distribution could have been manipulated to bring a PML-N backed CM, for which JUI-F had tried very hard. But many believe that PML-N wanted to take the wind out of the “tabdeeli” promises of PTI, and therefore allowed PTI to govern KP.

Goes without saying that if the electoral results of 2013 are exactly repeated in 2018, PML-N is not likely to allow PTI a second term. Therefore, the two most probable scenarios for PTI to win a second term in KP are; 1- PTI wins the center and at-least 15-20% of the seats in KP, 2- PTI pulls an MMA and gains a majority in KP.

Pulling an MMA would be difficult because PTI’s support base lies mostly in the incumbency punishing districts of Peshawar valley and Swat; 27 out of PTI’s 35 seats are from this region. To get an idea of the reliability of these seats, consider the fact that 13 of these 27 constituencies that opted for PTI in 2013, also opted for ANP in 2008 and MMA in 2002.

In terms of development spending, Pervez Khattak’s government has largely prioritized its Peshawar valley support base at the expense of other regions. But history suggests that such positive biases towards Peshawar valley have not yielded results come re-election time. Both Aftab Sherpao and Haider Hoti, were known for their preference for Peshawar valley and more specifically their home districts. But that didn’t mean much for their parties on their re-election days. PPP’s Peshawar valley results in 1990 and 1997 were not that different from that of ANP in 2013.

This is at a contrast to how southern districts responded to Akram Durrani’s prioritization of the South. In 2008, When MMA was being wiped out from the rest of the province, it won 6 out of 18 contested seats in the South. And in 2013 when PTI was sweeping Peshawar valley, JUI-F increased its share in the South from 6 to 9 seats. Similarly, PML-N’s favorable bias towards Hazara during their terms might explain why the region has been a consistent stronghold for PML-N.

PTI’s challenge is to not only maintain its incumbency-punishing support base, but to also break into the strongholds of both PML-N and JUI-F. Pervez Khattak’s prioritization of Peshawar valley is likely to make it difficult for his party to do the latter, but one can only wonder if it would be of any help with the former either.

This piece was published in the The News on 22nd November 2017

PTI and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

The Chief Minister of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa surprised many when he declared that “Pathans are PTI, and PTI is Pathan.” One could expect the leadership of ANP and PkMAP to say something to that effect because they are engaged in Pashtun identity politics. However it was strange to hear such a statement from a federalist party like PTI.

A factual response came from Chaudhry Nisar who simply quoted Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s distribution of votes in the 2013 general elections; PTI received 19% of the vote, a close second was PML-N at 16%, followed by JUI-F at 15%, ANP at 10% and JI at 7%. Thus making the point that PTI is not the only political force in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

It would also be incorrect to equate PTI’s popularity in KP to that of PML-N’s in Punjab or the PPP’s in Sindh. In terms of votes, PTI received 19% of the vote in KP and an almost equivalent proportion i.e. 18% in Punjab. However, in Punjab PTI was up against PML-N which secured 41% of the vote unlike in Pakhtunkhwa where the opposition vote was split up among several parties, as detailed above.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is unique in the sense that it does not have any one party with an overwhelming majority. Consider the 2008 elections, ANP received 17% of the vote and was able to form government. By 2013, its incumbency had cost it 7% of the vote and it was replaced by PTI. But, Pakhtunkhwa is not unique in exacting incumbency costs, Sindh too punished PPP, and perhaps more severely as PPP’s share of votes fell by 9%. But that meant a drop from 42% to 33%, still enabling PPP to retain the government in Sindh.

It is also a bit of an exaggeration to claim that PTI is overwhelmingly “Pathan”. In the General elections of 2013 PTI received approximately 5 million (50 lakh) votes in Punjab, in comparison it got only 1 million (10 lakh) in KP. But despite having 5 times the support in Punjab, it is very peculiar that PTI relies overwhelmingly on KP when displaying its street power, even when the planned display of power is in the Potohar region of Punjab (read Islamabad). The built up to the 2nd November protest was marked with anticipation for arrival of support from KP. Ironically, even the leaders from Punjab were looking towards Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. What could explain this obvious over representation of Pashtuns in PTI jalsas and dharnas?

One possible reason could be PTI’s championing of Pashtun causes. But that’s not the case, neither “rigging allegations in Punjab” nor “Panama leaks” have any particular significance to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. In fact on issues specific to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Imran Khan has shied away from supporting his KP leadership especially where there are potential political costs in Punjab.

For instance on the issue of Kalabagh dam, Imran Khan has taken positions from supporting it out-rightly to a support based on provincial consensus. In contrast, Pervez Khattak has recently declared Kalabagh a “dead horse” and a plan to destroy Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Similarly the Western route of CPEC is a key issue for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s Pashtun belt, but only a week after Pervez Khattak announced that he will not allow the CPEC through KP, Imran Khan assured the Chinese ambassador that his November 2nd protest was not about CPEC, a protest for which he was relying almost entirely on his support base in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Could it be that PTI’s KP leadership is more capable than its Punjab leadership? Well, is Pervez Khattak a better orator than Shah Mehmood Qureshi? Does Shahram Tarakai have deeper pockets than Jehangir Tareen? Is Shah Farman more popular than Asad Umar? The answer to all these questions is probably in negative, and in my opinion the main factor that distinguishes PTI’s KP leadership from the Punjab leaders is the KP government.

The KP government enables Pervez Khattak’s team to use political patronage to drum up man power for protests. During the recent LG polls in KP, a video of KP’s health minister Shahram Tarakai was making the rounds, in it Mr. Tarakai was demanding electoral support in return for infrastructure development done through public funds. This ability to use carrot and stick tactics for crowd mobilization is likely to be a crucial strength for PTI, which might have been instrumental in ensuring KP’s over representation in PTI events outside of KP whether it was the first dharna, jalsas in Punjab, and more recently in the second dharna/yom-e-tashakur. Since 2013, the leadership of PTI in KP seems to have out done their counterparts in Punjab in providing PTI’s street power, and not just in KP but in Punjab as well.

The live visuals from the confrontation between Punjab police and PTI’s Pashtun supporters generated two different sets of generalizations; PTI supporters resorted to romanticization of Pashtun loyalty and bravery while PTI opponents resorted to caricaturization of Pashtun naiveté.

However the reality might be much less generalizable, a procession of 5 to 6 thousand people can hardly be taken as representative of Pashtuns, and neither is its mobilization that big a task for a provincial government. Given the electoral history of KP as well as Imran Khan’s focus on Punjab it is likely that PTI might lose this crucial advantage after 2018. It will be interesting to see how that will affect PTI’s nuisance value, a characteristic that has defined its politics since 2013.

Published under the title “Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the PTI” in The News on the 4th of November 2016.

Jaag Punjabi Jaag

Recently a school notice has been making the rounds on social media. In it, the headmaster of a posh school in Sahiwal has warned children against using foul language at school. While there is nothing wrong with that, it’s the definition of foul language that has caused a stir; the notice defines it as “taunts, abuses, Punjabi and the (sic) hate speech”. In response to the backlash the school has issued a disclaimer and apology of sorts, and it seems likely that this was a mistake.

However, it would be wrong to assume that calling Punjabi a “foul language” is that big an issue in Pakistan. Tune into late-night comedy shows such as ‘Khabardar’ and the same is being done under the guise of comedy. You are likely to hear the very popular hosts of such shows scolding their colleagues for speaking Punjabi or Punjabi accented Urdu. The irony is that these shows make money by doing comical skits in Punjabi. Yet, despite that, their scripts disparage Punjabi as an uncouth (read ‘paindu’) language.

It is obvious from the popularity of the show that it’s largely Punjabi audience agrees with Punjabi being a language that is mostly appropriate for insults and jokes. But is that really true?

Punjab has a rich culture which has spread outside the confines of Punjab. Take bhangra for instance, its music and dance steps have become a staple for weddings from Muzaffarabad to Mumbai and Peshawar to Calcutta. Similarly, Punjabi literature and poetry can stand its own against the literature and poetry of any other language. This is the language chosen by the likes of Sultan Bahu, Bulleh Shah, Waris Shah, Munir Niazi and many other literary giants, surely their contribution can’t be termed uncouth and lewd.

But despite having all that, Punjabi as a language is suffering in a country where Punjabis account for almost half the population. This neglect is evident from the number of newspaper and periodicals published in local languages in Pakistan. Latest statistics from Pakistan Bureau of Statistics show that for 2011 both Pashto and Sindhi had 17 newspapers and periodicals each but Punjabi only had seven. Consider the populations of speakers for each of these languages and in proportionate terms the share of Punjabi comes across as even smaller.

I strongly agree with the position that this is a consequence of our national obsession with defining Urdu as our only national language. It has somehow become a proof of patriotism to prefer Urdu to regional languages. I am no linguist but I think that this has greatly affected languages that are linguistically closer to Urdu, because for the speakers of these languages switching to Urdu is relatively easy. Punjabi isn’t the only one; Hindko too has suffered in a similar manner, where it is common to see educated Hindko-speaking parents preferring Urdu over Hindko when it comes to raising children, as speaking Hindko is often seen as a sign of a lack of education as well as a lack of sophistication.

Aside from losing out on the literary front, Pakistan has also failed to cash in on the benefits of Punjabi and other local languages in primary education. Research shows that children at primary level learn much better when taught in their native languages. These benefits aren’t obvious when one considers children from the middle or upper class households in Pakistan.

It is safe to assume that a child from that demographic would have educated parents who are fluent in Urdu if not English as well. The child would also have the benefit of pre-school preparations whether through educational toys or TV shows. When such children start school, they carry the benefits of their privileged birth and are well prepared for learning in Urdu or English.

In contrast, a child from the more underprivileged sections of our society usually is born to parents whose language fluency is limited to their local languages. Such children are likely to not have had much exposure to either Urdu or English during their pre-school years. The main asset that such children bring to school is an understanding of their local language. Under our current education system we rob such underprivileged children of their one advantage, and instead make them learn a new language and also expect them to learn science and math in that same new language. And the level of difficulty is even higher for children whose native languages, in linguistic terms, are farther from Urdu, for instance Pashto, Brahvi, Sheena etc.

In post 18th Amendment Pakistan, provinces have the freedom to make changes regarding education within their domain. The ANP government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa introduced native languages as a medium of instruction at primary level in almost all the local languages in the province. However, the recently elected PTI government decided to roll back those changes and instead introduced English as a medium of instruction in order to implement the standards of Aitchison College. It was lost on the policymakers that to implement the standards of Aitchison, you just don’t need a curriculum but also teachers who are as qualified as those at Aitchison – along with a privileged upbringing for the children, which is the hallmark of the children studying at Aitchison.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa CM Pervez Khattak once said “when I hear about education in Pashto there is an explosion in my head”. It is obvious that denigrating local languages comes with little political consequences because such acts have become somewhat of a proof of patriotism. This has to change.

The lesson that we should have learnt from the fall out of the Bangla bhasha debate is that for our unity we need to celebrate our diversity rather than negate it. And for that to happen it is essential that the provincial identity and language of our majority ethnicity be recognised and respected. Only then would the championing of smaller ethnic identities not be seen as a threat to our national identity but rather a source of its strength.

Published in The News on 18th October 2016 under the title “‘Foul’ Punjabi”

Redefining Shame.

If there is one good thing that came out of the horrors of Kasur, it is that it has encouraged victims in other parts of the country to speak up; the family of a victim in Multan was the first to follow. Sadly, ours is one of those societies in which claiming victimhood for sexual assault unleashes a new set of social costs, the fear of which silences many.

The fact that Kasur families were paying to hide the victimhood of their children, shows that there is a great need for sensitisation of our masses regarding victims of child abuse. This lack of sensitisation probably emanates from the fact that we shy away from discussing paedophilia on more serious forums.

However, it would be wrong to believe that paedophilia is not discussed in Pakistan. When topics are deemed taboo for official forums, they usually become a source of humour on more unofficial ones. While that is understandable in the case of toilet humour, it is tragic to consider that we have the same approach towards child abuse.

It would be very unlikely for anyone reading this to have not received an SMSed joke about a Khan Sahib lusting after a young boy. While the jokes are insensitive and offensive, the more ridiculous part, however, is that for many this understanding is not limited to jokes. A Channel 4 documentary that came out some time back showed the plight of sexually victimised street children in Peshawar. Rather than generating debate on the need to protect these children, the documentary got criticised for its title ‘Pakistan’s hidden shame’, which according to many should have been ‘Peshawar’s Hidden Shame’.

However, as Sahil’s ‘Cruel Numbers’ reports for 2012, 2013, and 2014 show, the provincial incidence of reported sexual assaults on children has been the highest in Punjab. It would be ridiculous to now label all Punjabis as potential paedophiles, because the provincial statistics mirror the population size for each province. Punjab shows the highest incidence because it has the biggest population. This data makes one thing clear – that paedophilia is a problem for all of Pakistan, and not just one province.

In the aftermath of Kasur, weaknesses in policing and judiciary are being quoted as the main reasons behind our failure to stop these incidents. There is no doubt that better policing and quicker punishment for culprits would set effective examples, but these two institutions mostly get involved after the child has gone through the ordeal. Can we say that, with our norms of parenting, we prepare our children well enough on how to react to sexual predators?

The fact is that in most households, sex related topics are avoided and usually the best advice offered to children is to warn them against strangers. However, of the cases reported during 2002 to 2006, 76% of assaults were carried out by individuals who already knew the children. A Sahil report observes that children aged 11 to 15 years are the most vulnerable, because at puberty they are curious about physical and sexual changes in their body. But due to the taboo surrounding these discussions they are likely to seek more willing adults for answers, and those adults might not necessarily mean no harm to the children.

Not only do most of our children lack awareness on how to face paedophiles, they also face castigation if they become victims. One famous TV anchor recently compared the victims of Kasur to the martyred children of APS. He was of the opinion that the children of APS were better off compared to the children of Kasur, since the former are in heaven, while the latter and their families won’t be able to “show their faces” for the rest of their lives.

It is this kind of ignorance that permeates our society. Why exactly should these children not be able to show their faces? Should victims of robberies not show their faces because they should be ashamed that they were robbed? Should murdered individuals be buried secretly as there is shame associated with their murder? Why single out the victims of sexual abuse as those who should face social consequences post victimisation? Is it the victims who should be ashamed or the society that marks them with shame?

Paedophiles and rapists are not unique to Pakistan. Just like murderers and thieves, they are part of every society. But what distinguishes societies is the way in which they treat victims of paedophilia and rape. In our society, rapists and paedophiles are faced with potential victims who would be too ashamed to point a finger at them. It is this shame that is the paedophile’s biggest advantage.

Our children need to be assured that their acceptance is not dependent upon a lack of victimhood. And the only way to do this is for us to start educating them about their vulnerability as well as the support that they can rely on. Furthermore, we need to take the ‘humour’ out of paedophilia and deal with it with the seriousness it deserves. As a society we need to realise that it was our definition of shame that silenced the abused children of Kasur.

Patriotic Provincialism

As the PML-N celebrates Pakistan’s reaffirmed ‘iron friendship’ with China, it is also warning about the potential rusting of this friendship thanks to some nagging entities of the provincial variety.

Ahsan Iqbal’s advice to the ANP is to not politicise the issue of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) as it is important for the future of Pakistan, and, as an added benefit, is also giving insomnia to Pakistan’s enemies. Thus to be recognised as a patriotic well-wisher of Pakistan, one has to say it out loud that the benefits from the CPEC are to be shared by all of Pakistan – for a better future, that is.

Fair point, the future is important, but then should it be that convenient to forget the past and its regional distribution of miseries? The world is often reminded that Pakistan is the ‘frontline state’ in the war against terror, but similar reminders about the ‘frontline region’ within Pakistan are rarely mentioned.

Be it bombings, beheadings, kidnappings, amputations or whatever variable that can measure the cost of the war on terror, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Fata have paid far more than the rest of the country combined. And I pray that Punjab or for that matter any other place never ever pay the price that has been paid by Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Fata.

But good wishes for the future do not change the past. And a past that has been stained with the blood of thousands should not be that easy to forget. The costs paid by KP and Fata were a result of Pakistan’s jihad experiments, which have now been owned by retired generals Musharaf and Durrani. It is understandable that the PML-N government is helpless in bringing the planners of these policies to justice, but it would be completely shameful if it also ignores the plight of the victims of these policies.

To quote Khwaja Asif ‘O koi sharm karo, koi haya karo’. The state of Pakistan owes a lot to the people of KP and Fata for what it has unleashed upon them in the name of ‘strategic interests’, and ensuring the revival of their economy is the very least that Islamabad can do as penance.

To give Ahsan Iqbal credit, he does assure everyone that a route through Khyber Pakhtunkhwa will be operational. But then, should verbal assurances backed by a line on a map be enough proof for that? Why is it that out of the 21 projects earmarked for the CPEC in PSDP of 2014-15, not even one is in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa?

Similarly, in the recent deals with China, the only funds destined for the CPEC in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are for the dry port at Havelian. But that dry port is also essential for the eastern route, and besides that nothing else is being earmarked for the western route that goes through KP. Is the western route in such good shape that no investment in infrastructure is needed for it? Furthermore, China’s state television CCTV is also reporting only one route which passes through Punjab, and makes no mention of the PML-N’s promised route for the people of KP and Fata.

The steadily increasing outward migration from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Fata is a clear indicator that the economy of this region is failing its people. If patriotism means safeguarding the best interest of Pakistan, then the need is to prioritise the economic revival of this region, rather than lash out at those who are highlighting this need. There is no competition between Punjab and KP when it comes to the level of road infrastructure as well as security. Therefore it is very likely that even if both the routes are open, the eastern route might be the obvious choice.

An Islamabad with no provincial biases would have prioritised the plight and desperation of the Pakistanis of KP and Fata over everything else. It would have seized this opportunity to sell the western route to the Chinese as the only route, and also ensured that all objections to that route are taken care of. But it has completely failed in doing so and there is no evidence of the PML-N even trying for that.

This issue of the CPEC has been taken up by a number of political parties now, but at the core of this resistance is a group of Pashtun nationalists. This is mostly the same group that recently raised the issue of mistreatment of the IDPs. Before that they were speaking out against the ‘good’ Taliban, and a long time back the antecedents of this group were warning about the use of jihadis as a tool of foreign policy.

Most, if not all, of their demands have been received with either indifference or suspicion at the national level. And resultantly, since much of their protests have been in vain, this latest one on the CPEC is likely to suffer the same fate. To many, the irrelevance of these ‘provincial’ voices is necessary for strengthening this federation. But this view ignores the fact that these Pakistani Pakhtun nationalists make their claim for rights as Pakistani citizens. They do not reject the state of Pakistan, and make their demands through constitutional means.

The increasing irrelevance of Pakistani Pakhtun nationalists in the national discourse is coupled with their growing irrelevance in their own constituencies as well. It is becoming difficult for parties such as ANP and PkMAP to sell the idea that Pakhtuns can get their rights by using constitutional means within this federation.

Considering that the underlying problems still persist, it is quite possible that the vacuum left by these parties could be filled with Pakhtun nationalism of the separatist kind. We are currently witnessing the consequences of the irrelevance of Pakistani Baloch nationalists. Let’s not repeat the same mistakes with the Pakhtuns as well.